|

December marks time like no other month.

Tomorrow the winter solstice brings us the shortest day of the year followed by the longest night ... and days later, the end of one year and the beginning of another. I’m thinking about how I can add light to my days and mark new beginnings. Not just new beginnings on the calendar, or the light from longer days, but the light and change that comes from doing things differently, seeing things in new light, and being curious. Last week we had a snow storm ... a big one. Most of us got anywhere from 18 - 24 inches. And as it so often happens, the next day it was glorious. Sunny and bright and fresh. After the storm, we took a ride ... uptown to State Street, left at Longfellow Square ... and there it was. A rainbow. Shimmering in the windblown snow hanging in the air. This week's calendar ... Thursday is Egg Nog Day. Are you a fan? You'll also see that today is Poet Laureate Day. Because the statue in the rainbow photograph is poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, I want to share a post I did a while ago on blackout poetry. Follow this link to read more about Longfellow and blackout poetry, and give it a try. Use it to create a poem. Stick it to the refrigerator or mail it to someone. It may add new light to your day. After all, you could be a poet and don't even know it. Even if you don't want to try the exercise, click through to read Longfellow's poem, Holidays anyway. It's fitting for this holiday season ... one that is so very different from so many others. Read it and let me know what you think. And if you create a poem, share it with me. I'd love to read it. p.s. There's also a link in the post to Robert Frost's poem Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening. You can read the poem and find out why it's one of my favorites.

0 Comments

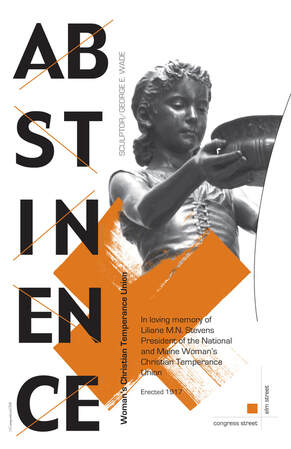

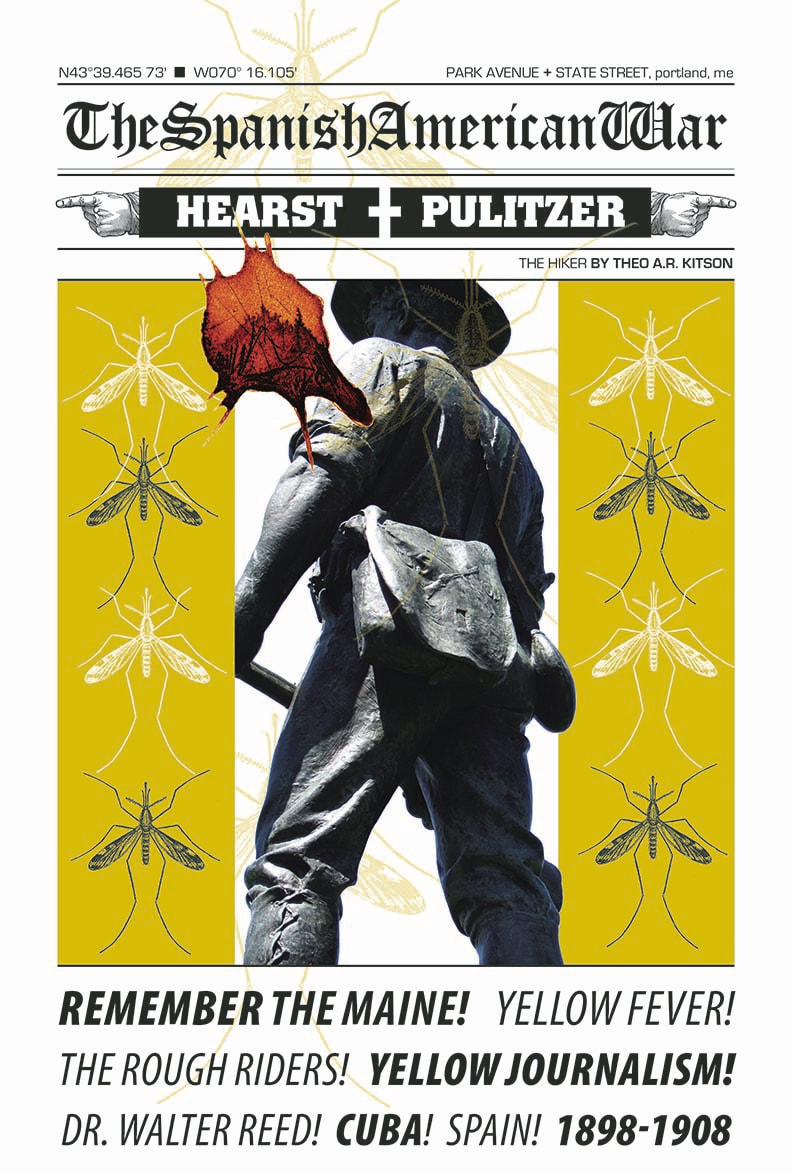

Sundials: fighting time and finding patience On our morning walk we passed a sundial and the urge to check the time was irresitible. The arrow (or the gnomon as the shadow-casting feature on a sundial is called) indicated it was just after 7:00. We were confused. It was, we knew, just after 8:00. It took us a split second(!) to realize sundials, of course, don’t recognize Daylight Savings Time. The sundial moved more than time Seeing the sundial made me think more about time. How we spend it, how we fight with it, and how it teases us. When I got home, I was reminded once again, that I need to be patient. That whatever hobbies, passions, and pastimes we choose, they need time to build and develop. Just a week after I started my illustrated journal, I decided to go with the sundial for a new page and collage. But I struggled. I sketched the idea and started cutting bits of paper, but it wasn’t working. The proportions were off and even though one of the things I like most about collage is that it’s perfectly imperfect, it still needs to look like something close to what it represents. I wanted to give up and walk away because things weren’t going my way. But I didn’t. I stayed with it, and the more I worked on it, things began to shift. The idea of the sun as a background element came, then adding the minute and hour hands seemed like a good idea. It was slow going, but with each idea, my confidence grew and I forgot about the time, and the struggle. Lesson learned When I was done, I knew there was a lesson somewhere, and it seems, the lesson is: things take time. When I sat down I was frustrated and wanted my collage to come together quickly. Clearly, that wasn’t going to happen. My mind needed time to process the concept and figure things out. But that’s not all. The sundial set me on a course of unexpected curiosity, offering a couple of other lessons: You never know where something may lead When we got home, we were curious about sundials. We learned that sundials are the “earliest timekeeping device” and the element that casts a shadow is the gnomon. It gave us renewed appreciation for sculpture, the stars, the sun, and the moon. Hang in there When I started the collage I was impatient. Things were taking longer than expected and I wanted to give up. But when I finished, nearly two hours later, I felt better. More relaxed and (really) happy that I stayed with it. How often do you fight with time? Are there lessons you’ve learned from sticking with something? Tell me about it. The first time I saw her, she was tucked in a corner behind bars in the entryway to the Portland Public Library. I might not have noticed her that day, or any other, if it wasn’t for the whirlwind of dried leaves and rubbish swirling at the base of the statue. It was the Little Water Girl, a charming bronze statue of a young girl, and I wondered who she was. I did some research and found an amazing story, and it made me wonder about other statues in the city. There’s the The Hiker in Deering Oaks park, the Lobsterman in Canal Plaza, filmmaker John Ford in Gorham’s Corner, and poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in Congress Square. Each one revealing more history and intrigue than I could have imagined. I uncovered information about a poet and a filmmaker, yellow journalism, a horse named Madge, Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, air pollution, prohibition, and the World’s Fair. After doing my research, I wanted a record of what I found, so I wrote essays and created posters for some of the statues. Here are three of them. Little Water Girl Barefoot with outstretched arms, the Little Water Girl is a fitting tribute to the legacy of Lillian Stevens, a dedicated advocate for women and children, and the third president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The WCTU Founded in 1874, to “combat the destructive powers of alcohol and the problems it was causing their families and society,” the WCTU banded together in prayer, protest, and pledge—a pledge of total abstinence from alcohol. Prohibition and Water Fountains In an effort to curb the temptation of saloons the WCTU fought for Prohibition, encouraging members to install public drinking fountains in their communities where “men could get a drink of water without entering saloons and staying for stronger drinks.” The Little Water Girl is one of those fountains. In support of the WCTU, Lillian Stevens a committed and independent woman, traveled by carriage with her horse Madge some 50,000 miles lobbying for Prohibition. Ratified five years after Stevens’s death, Prohibition didn't last, but more than 70 fountains inspired by the WCTU initiative remain standing across the United States, in Canada, England, and Australia. The Little Water Girl by British sculptor George E. Wade was commissioned by the WCTU for display at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893. Copies of statue can be found in Chicago, Detroit, and London. Note: Why was the Little Water Girl behind bars? She was moved to the secure, gated entrance to the Portland Public Library after she was vandalized in Deering Oaks park. When the library was renovated, the Little Water Girl was restored as a working fountain and moved inside. Today she greets patrons as they enter the library. The Hiker Although the Hiker is larger than life and perched on a six-foot pedestal, the Spanish War Veterans memorial on the north lawn of Deering Oaks Park is easy to overlook. But do look—it’s a beautiful statue. From the soldier’s wadded and rolled sleeves to the leather satchel reminiscent of today’s messenger bag, the details are captivating. The Hiker is sculptor Theo A.R. Kitson’s most well-known work—more than 50 copies of the statue are installed across the country. Under the rallying cry “Remember the Maine,” the Spanish-American War secured Cuba’s independence and remains one of the shortest wars on record. But that’s only the beginning. Dig a little deeper and fascinating tales of science, circumstance, and cowboys emerge. For it was during the Spanish-American War that army medical scientist Dr. Walter Reed isolated the cause and stemmed the transmission of yellow fever plaguing the troops; eager journalists and competing publishing magnates gave rise to the dirty business of yellow journalism; and Teddy Roosevelt’s volunteer militia, The Rough Riders, found glory. It was a short war, but a war with a decidedly jaundice pallor. Note: There were at least 50 copies of The Hiker cast and placed in cities across the United States from Texas to Minnesota, and Georgia to Maine. Here’s a list of cities where The Hiker was installed. See if there’s one where you live. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow He broke bread and corresponded with the likes of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Oscar Wilde, and Charles Dickens. Born in Portland, Maine, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was a linguist, professor, and poet. A graduate of Bowdoin College, Longfellow yearned for a life in literature. And so it was. Under agreement with his alma mater, he set out across the Atlantic to study European language and literature. He would return to teach at Bowdoin and then at Harvard College, but writing would prove to be his vocation. Longfellow's well-known works include Evangeline, “The Wreck of the Hesperus,” and “Paul Revere’s Ride. He was a best-selling author and enjoyed considerable success with his work but he suffered tremendous loss in his personal life. His first wife and childhood friend, Mary Storer Potter, died following a miscarriage. And his second wife, Fanny Appleton, with whom he had six children, died after setting her dressing gown afire with candle wax. Forever saddened, Longfellow did little writing after Fanny’s death. Sculptor Franklin Simmons’s bearded Longfellow sits with a stack of books at his feet and scroll in hand. Like Longfellow, Simmons was born in Maine and became a well-known artist in his day. A second sculpture by Simmons, Our Lady of Victories stands just blocks away in Monument Square in downtown Portland. How could you interpret statues and landmarks where you live? |

Whistlestop Blog

Enjoy a story and find inspiration to write one of your own. Categories

All

|